Although we may think of paper money as a fact of life today, for much of American history paper money was contentious and controversial subject.

In the years prior to the American Civil War, individual banks issued a wide variety of paper money across the United States. Many banks were weak and prone to failure as the banking sector in many states was unregulated, which led to a string of fraudulent banks that issued notes with false pledges of real estate or other securities. As such, paper money was distrusted by the average American in the Antebellum period and there was a strong preference for hard money.

After the Civil War started, the United States faced a severe shortage of circulating specie, which in turn led to the suspension of specie payments, which made government-issued “Demand Notes” that were backed in coin unredeemable in practice, and subject to hoarding by speculators and the general public.

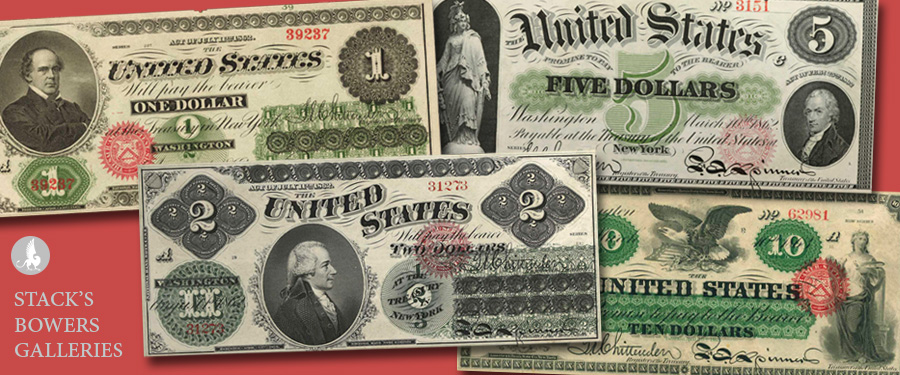

As a result, the federal government introduced Legal Tender Notes. The first of these, issued as part of the “Series of 1862” and “Series of 1863,” bore denominations of $1 through $1,000 and were part of an $150,000,000 emission in the early months of 1862. These notes displayed famous Americans such as Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase and President Abraham Lincoln, as well as obscure personalities like Albert Gallatin or an allegorical representation of Liberty as seen on the $20. These notes were printed using a dark green ink on the reverse leading to the moniker “Greenback” being used frequently in public discourse.

Shortly after their adoption, “Greenbacks” were met with lukewarm acceptance by the public and traded below face value. They continued to face headwinds especially as the government increased circulation again in 1863. In 1864 circumstances were at their worst, as legal tender notes traded at an all-time low of roughly 39 cents on the dollar, following a string of Confederate victories and the passage of the Anti-Gold Futures Act of 1864. Even after the conflict, “Greenbacks” continued to trade at a discount compared to coins and were entirely disfavored in the West until the Specie Payment Resumption Act of 1875 went into effect on New Year’s Day 1879.

Today these “Greenbacks” are relatively common on the market and those denominated $1, $2, $5, and $10 can be located with relative ease. Higher denominations are scarcely encountered except for the $20 which trades at a strong premium. However, most examples of the type have problems and are frequently assigned net/details grades.

To consign your numismatic items to one of our upcoming auctions, please call 800-458-4646 or email Info@StacksBowers.com.