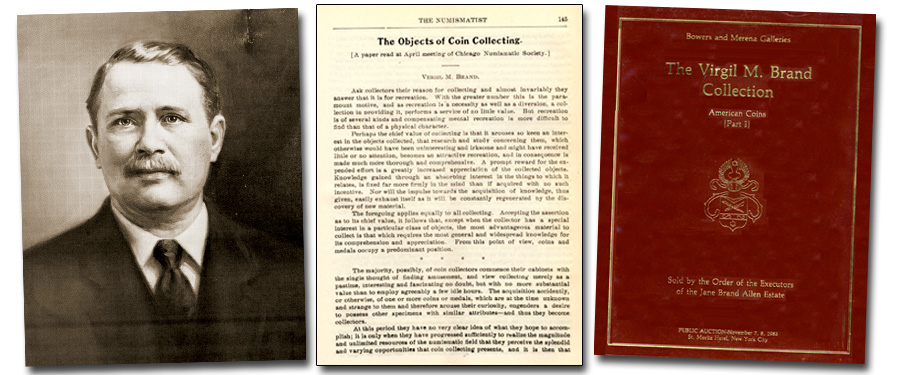

One of my favorite numismatic experiences was working with Norman Neubauer, the Morgan Guaranty Trust Company, the heirs of Virgil M. Brand, and David E. Tripp in the sale by auction of many coins from the Brand estate. If you are an old-timer, you will remember these events in the 1980s. Particularly challenging for me was writing a book, Virgil Brand: The Man and His Era. For starters, conventional wisdom among numismatic scholars in the 1980s was that Brand, a wealthy Chicago brewer, spent a lot of money on coins, but that was about it.

With a lot of searching through Brand family documents and other sources a different picture emerged: he was one of the leading scholars of his era – the late 19th and early 20th centuries – was often called upon to determine coin authenticity, contributed comments to The Numismatist, and more. If you have a chance to find a copy of my book in the hands of a numismatic bookseller or on the Internet, I think you will have a “good read.”

That said, I share excerpts from an article by Brand that appeared years ago in The Numismatist, May 1905:

The Objects of Coin Collecting

Virgil M. Brand

Ask collectors their reason for collecting and almost invariably they answer that it is for recreation. With the greater number this is the paramount motive, and as recreation is a necessity as well as a diversion, a collection in providing it, provides a service of no little value. But recreation is of several kinds, and compensating mental recreation is more difficult to find than that of a physical character.

Perhaps the chief value of collecting is that it arouses so keen an interest in the objects collected, that research and study concerning them, which otherwise would have been uninteresting and irksome and might have received little or no attention, becomes an attractive recreation, and in consequence made much more thorough and comprehensive. A prompt reward for the expended effort is a greatly increased appreciation of the collected objects. Knowledge gained through an absorbing interest in the things to which it relates, is fixed far more firmly in the mind than if acquired with no such incentive. Nor will the impulse toward the acquisition of knowledge, thus given, easily exhaust itself as it will be constantly regenerated by the discovery of new material.

The majority, possibly, of coin collectors commence their cabinets with the single thought of finding amusement, and view collecting merely as a pastime, interesting and fascinating, but with no more substantial value than to employ agreeably a few idle hours. The acquisition accidentally or otherwise, of one or more coins or medals, which are at the time unknown and strange to them and therefore arouse their curiosity, engenders a desire to possess other specimens with similar attributes—and thus they become collectors.

At this period they have no very clear idea of what they hope to accomplish; it is only when they have progressed sufficiently to realize the magnitude and unlimited resources of the numismatic field that they perceive the splendid and varying opportunities that coin collecting presents, and it is then that they define more clearly to themselves the objects and purposes for which they henceforth collect.

Naturally these will differ greatly and will vary according to the inclination of the individual, depending upon which features of numismatics appeal to him most forcibly. Some will find the speculative possibilities the greatest attraction and will collect only for the purpose of financial gain; these, however, should be considered dealers, rather than collectors.

Many restrict their efforts to coins of a selected period or locality, or of a certain metal or denomination, or gather only specimens relating to one or more separate related subjects. Collectors adopt a great variety of limitations, some of them unique. For example, one collector confined himself to coins from dies with errors, another to those bearing representations of animals, and still another limited the animals to elephants. But all, no matter how much they have restricted their field, realize early in their collecting experience that in order to proceed intelligently and arrive at a proper and thorough comprehension of their coins, research and study more or less exhaustive is imperative. To the collector’s zeal is now added a craving for knowledge, and his cabinet becomes a powerful and valuable influence in favor of education.

The branches of learning to which the science of numismatics is related are numerous, and many collectors specialize, selecting one or more of them, according to their inclination or interest. It is a part of archaeology and is a valuable aid in the study of mythology, heraldry, iconography, and other subjects. But its relation is closest to history; in fact coins have been freely employed in revising the latter, and much valuable historical data rests entirely upon their testimony.

In the domain of art, coins and medals occupy an important place. They furnish instantaneous ocular proof of the attained stage in its development at all times, and are unimpeachable contemporaneous witnesses to its progress. Nothing will illustrate more strikingly the advance of art, from the crude attempts in the earliest times until it reached its greatest perfection, centuries later—its gradual decline and almost total eclipse during the darkness and turmoil of the Middle Ages and its rejuvenation thereafter, than a series of coins covering the period involved. The features of numerous historical personages, as well as the costumes worn in past ages, are known to us only from coins and medals, on which they are faithfully reproduced by contemporary artists.

The economist may be chiefly interested in coins as money and will find his cabinet indispensable in the study of the monetary systems of nations, the relative value of the precious metals at various periods, the fineness and weights of the world’s coins, and the purchasing power at different times and in different localities.

The true numismatist, while he may specialize in a kind or class of coins, does not do so in his researches concerning those he collects, but strives to acquire a full knowledge of everything pertaining to them. He notes the size, weight, composition, shape and date of issue of each specimen and learns its name and place in the monetary system of the times. He investigates the causes of its rarity, if it is rare—due perhaps to it being one of the small emission or of a recalled issue—and if the latter he tries to learn the cause for the recall.

To the uninitiated, all of this may seem a formidable task, but in reality it is far from being so. Careful study of the history of the nation or other authority issuing the coins will yield the greater part of the desired information; some portions of it, of course, must be derived from special sources, and this last applies peculiarly to researches concerning coins issued without the sanction of any constituted authority (private coins).

The above points are worth considering.