It must be apparent to those who have followed my stories about my "teenage collecting” that numismatics wasn’t an easy hobby for many, as in most cases it required money to build a coin collection in this rough economic period. During this time, when rarer coins came up at auction or became available from a dealer, the advance in price was often minimal. There was little need for price information more than once a year.

As we moved into the late 1930s, money became less scarce, and at the end of each week there might be a little to set aside, pulling items from circulation. New U.S. coin designs — the Washington quarter in 1932, the Jefferson nickel in 1938, the Roosevelt dime in 1946 and the half dollar in 1948 — made the old designs more desirable when they could be found in spare change. Of course, as designs left circulation they became scarcer, and for some issues you might need to go to a coin dealer and buy one.

While coin collecting did not stop during the World War II years, much attention was diverted to the war effort and not to collecting. People often saved coins in jars, not in orderly collector albums. Only a few could continue to seriously collect so demand dropped and the market lost many buyers.

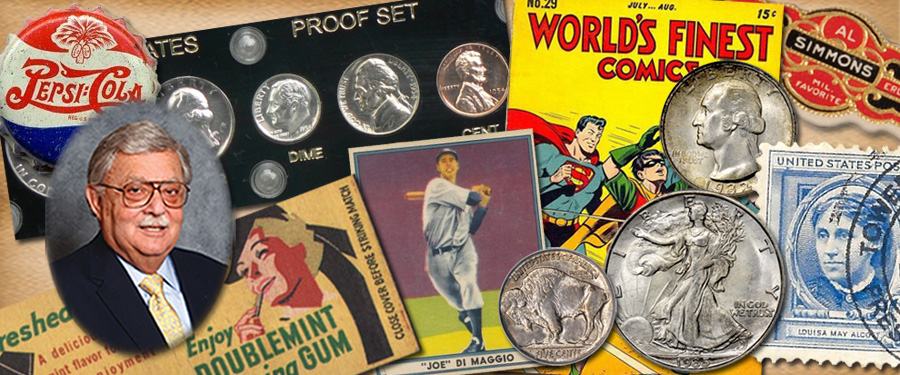

After the war, by 1950, the Mint started to make Proof coins again. They charged the public $2.10 for a set that included the 1¢, 5¢, 10¢, 25¢ and 50¢ (a total of 91¢ face value). The Mint made 51,000 boxed sets and, even at this relatively low price, they had a number leftover in 1951. Despite not selling out completely each year, the Mint increased the number made and by 1964, (the last year of silver coinage in the sets) they were making over three million sets per year. To insure they had enough to fill orders, they consistently overproduced. So the sets remained cheap during this period, and were sold not only to collectors, but also to the public, as the specially struck coins were attractive. The general public liked them for gifts, for birth years, birthdays, anniversaries, etc. The face value remained at 91¢ in each set, and the premium represented a reasonable price to commemorate an event. Many people who first learned about the hobby through Mint Proof sets went on to fall in love with coin collecting.

However, promoters offered Proof sets as an investment, often selling them at a profit to non-numismatists who did not know how inexpensively the sets could be acquired at the Mint. The promoters made good profits from the sales. The market shifted in the 1960s and early 1970s and some of these sets were sold off at below their issue price. “Investors” who had this experience could have a negative reaction to numismatics. Over the years, this scenario would play out again and again. The Mint continued to make coins with special finishes as a way to make a profit and to feed collector demand, sometimes resulting in disillusionment for those who felt they had gotten a bad deal.

However, some of those who became disenchanted with Proof sets, along with those who discovered the coin-collecting bug through those same Proof sets, often started to seek other things to collect within the field. It was then that I came into contact with these new collectors, when they came to Stack’s for help learning about coins and building collections.

More to come next week.