Used in the medicinal field for a millennium, people began to use opium recreationally in China in the 17th century when it was mixed with smoking tobacco. As the Chinese population grew, so too did the demand for this drug derived from the breadseed poppy plant. Along with this increase in demand came a trade imbalance between the imperial Qing dynasty and Great Britain. Chinese goods, such as tea and silk, were immensely popular in the west, and seemingly endless supplies of silver were received as payment for these exports. In order to counter the growing trade deficit, Great Britain—under the British East India Company—began to cultivate opium in India and illicitly smuggle it from that area into China, reversing the negative flow of goods.

In the process, the number of Chinese addicted to opium skyrocketed, causing great concern for the Daoguang Emperor. When attempts to appeal to the British failed, a blockade ensued, halting foreign ships including opium imports. This action resulted in the First Opium War, which lasted nearly three years from 1839–1842. The British emerged victorious, opening more Chinese ports for trade, receiving Hong Kong Island (the control of which they would maintain until 1997), and continuing the supply of opium into the vast Chinese empire. Toward the end of the 19th century, domestic opium production overtook foreign import of the drug, allowing the Qing dynasty to control consumption, finally suppressing its use to a degree. This respite was short-lived, however, as the dynasty—and the empire herself—fell to Republican and Nationalist sentiments. During the interwar period, the various factions around China began to rely heavily upon tax revenues from opium, causing its cultivation and consumption to again increase.

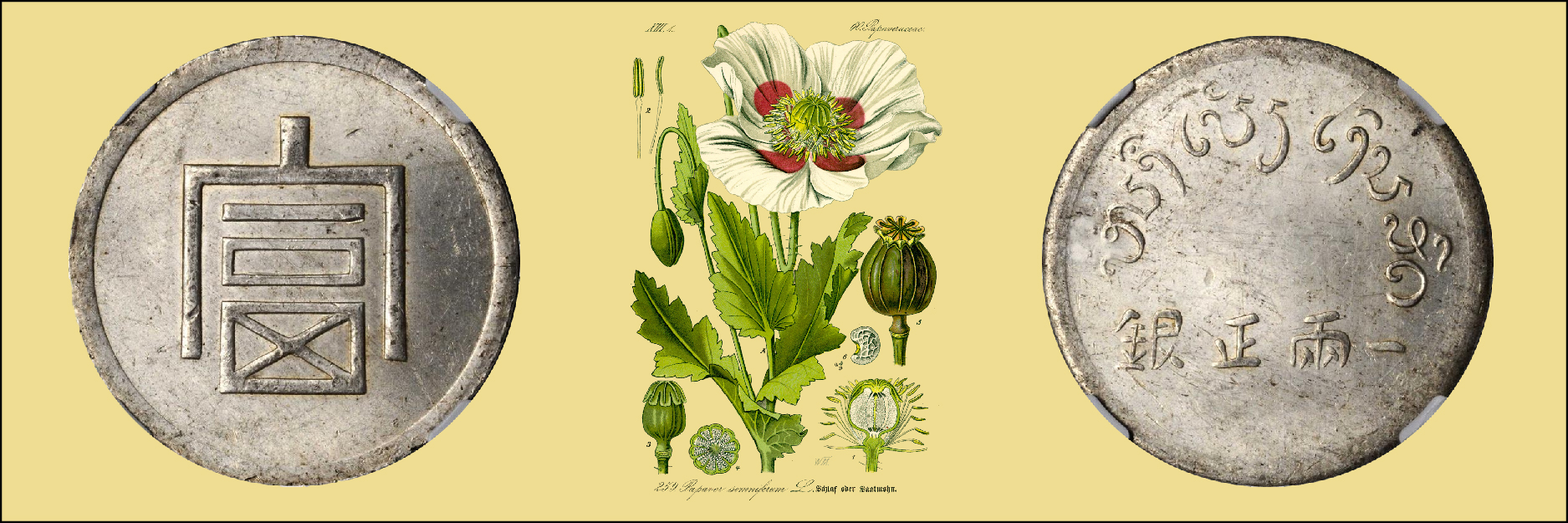

By the early 1940s, World War II drew much of the globe into regional strife. In Southeast Asia, the Japanese Empire—along with her cohorts Thailand and the State of Burma—attempted to cut off aid to China from her allies the United Kingdom and the United States. France, still a colonial power in the region, relied heavily upon tax revenue generated from the opium trade to fund French Indochina (comprising parts of modern-day China, Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam). With south-central Chinese trade routes nearly choked off by Japan, opium could no longer flow in from India and the Near East, creating an opportunity for France. Opium production in French Indochina was increased and the drug was allowed in through the colony’s shared border, the province of Yunnan. In order to further facilitate the trade, French provincial mints struck two types of tael coinage (the tael being a unit long recognized in and around China).

These taels, though rather minimalist in design, accomplished their goal perfectly. The reverses of each type featured a bilingual legend in both Chinese and Lao meaning "genuine silver, one tael," easily conveying their value across borders. For their obverses, one type employed a rather simplistic stag’s head (found in large and small sizes), while the other type simply displayed the Chinese character fù (富), meaning "wealth," formatted in a rather modern block script.

Lots 51517 to 51525 in our upcoming Stack’s Bowers and Ponterio Hong Kong auction will feature an enticing run of these enigmatic taels and half taels that circulated at the crossroads of a burgeoning international drug trade.

The post-war period saw an even greater rise in opium production and trade, especially as neighboring Burma gained independence from the United Kingdom. Further advancements in refinement decreased production costs and, by the 1970s, the narcotic was being smuggled into the United States where it ravaged segments of the population and fed an opioid epidemic that persists even today.

To view these interesting relics of the opium trade, along with the rest of our exceptional Hong Kong auction, please visit our Stack’s Bowers website where you may register and participate in this upcoming sale.

Although we are no longer accepting consignments for our August 2019 Hong Kong auction, we are always seeking interesting and exceptional coins, medals, and pieces of paper money for future sales, including our Collectors Choice Online (CCO) auction in October and our Official Auction of the N.Y.I.N.C. in January 2020. If you would like to learn more about consigning, whether a singular item or an entire collection, please contact one of our consignment directors today and we will assist you in achieving the best possible return on your material.