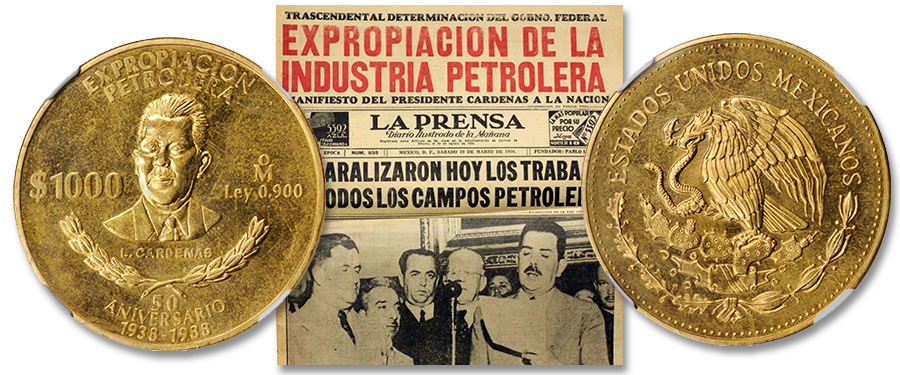

During the early 20th century, foreign investment in Mexico increased as the country emerged as a market, with interest in her natural resources chief among the pursuits. Foreign petroleum companies, such as those in the United States, Great Britain, and the Netherlands sought to maximize profits by taking advantage of low wages paid to the local Mexican workforce. In 1935, tired of their disadvantageous position, the Petroleum Workers Union issued a list of demands that included a 40-hour work week, sick pay in the event of workers’ illnesses, and an additional sum to be used for backpay and benefits. The foreign companies’ counterproposal was viewed as less than ideal, and a strike ultimately resulted. Though well received by the nation, the complete halt of oil production quickly became an issue throughout the country, and a cessation was brokered by Mexican president Lázaro Cárdenas while the issue was adjudicated by the court system. In the end, the courts sided with the labor union. Despite this, the foreign companies continued to balk at the demands, citing the financial distress that this would cause. What the companies failed to disclose, however, was that the profits generated from Mexico were greater than from other oil producing countries, such as the United States. They did, in fact, have the financial leeway to comply, but were unwilling to give up the lucrative position they had in Mexico. Cárdenas, seeing it as his only way to resolve the situation, declared that, on 18 March 1938, all mineral and oil reserves found within the borders of Mexico belonged to the nation, cutting out the foreign interests. International reception to the act was not favorable, though there was little real intervention, especially considering the rise of Hitler and Germany’s moves toward expansion. Domestically, the nationalization was highly popular and remains the policy for which Cárdenas is best known.

To mark the 50th anniversary of this monumental act, Mexico issued a series of commemorative coins in 1988 across five different denominations. Though three of the five are relatively common and quite easily obtainable, the remaining two—each in gold—are of the highest rarity and are only extremely infrequently encountered in the marketplace. The only such record of the gold 500 Pesos was in a 2014 fixed price list at the asking price of $5,000. Our current February World & Ancient Collectors Choice Online (CCO) sale features its larger and higher denominated counterpart, a gold 1000 Pesos, graded NGC MS-64. With just one other having been graded across both services—an NGC MS-65—it is easy to see how incredibly difficult locating another of these exceedingly rare and historically interesting issues would be. Given the benchmark of the smaller denomination set seven years ago, the heights to which the present example could be staggering.

To view our upcoming auction schedule and future offerings, please visit StacksBowers.com where you may register and participate in this and other forthcoming sales.

We are always seeking coins, medals, and paper money for our future auctions, and are currently accepting submissions for our June Collector’s Choice Online (CCO) auction as well as our Official Auction of the ANA World’s Fair of Money in August. If you would like to learn more about consigning, whether a singular item or an entire collection, please contact one of our consignment directors today and we will assist you in achieving the best possible return on your material.