By Q. David Bowers, Founder

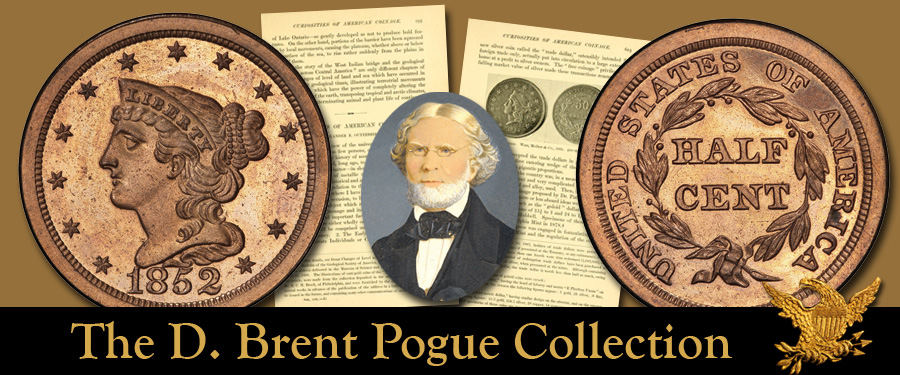

This marvelous 1852 half

cent is another treasure from the D. Brent Pogue Collection. It will cross the

auction block at our sale at the historic Evergreen Museum & Library in

Baltimore on Friday evening, March 31. You are invited to attend in person or,

if your schedule does not permit this, in virtual reality—real time—on the

Internet. Either way you will be part of numismatic history as it is being

made.

This marvelous 1852

Original half cent, thought to be the very finest of only four known, will be key

to a set of Braided Hair issues. Although Christian Gobrecht’s Braided Hair

motif was introduced on the $10 gold eagle of 1839 and large copper cents and

gold half eagles in 1839 it was not until 1840 that it was used on half cents.

From 1793 onward, half

cents and copper cents were the only denominations struck by the Mint for its

own profit. Silver and gold coins were minted as an accommodation to

depositors, and little if anything remained as profit. In contrast, the Mint

bought copper on the market and coined it into half cents and cents. The

difference between cost and face value translated to the bottom line as profit.

Popular numismatic

history has it that half cents were made in small quantities because they were

not popular with the public. That is not true. Many items were priced with half

cents being part, such as 12½ cents, the value of a Spanish silver real.

The main reason for the

small production of half cents in comparison to cents is that it was more

profitable for the Mint to coin one cent than two half cents. For precisely the

same reason, when the $20 double eagle became a reality in 1850, the Mint began

making more of these than of other denominations. It was more efficient to make

one double eagle than, say, eight quarter eagles or 20 gold dollars.

In 1840 there was numismatic

demand for Proof coins. Half cents were made in Proof format for inclusion in

such, a process that continued for years afterward. It was not until 1849 that

Braided Hair half cents were made for circulation, after which time production

continued until 1857, with the solitary exception of 1852, as per the coin here

offered. Half cents of 1852 were made only in Proof format. Nearly all in

existence today are restrikes. The marvelous original offered here is a

landmark.

Rare coins often have

stories, including about their past owners. For this coin John Kraljevich has

re-created a marvelous scenario, the essence of which is quoted below.

Warning! Reading the following might

inspire in you a love for numismatic history—which can use up a lot of time!

As you will see from the

provenance notes at the end of this narrative, decades ago this coin was

sold to R.L. Miles by Harry Forman, the resourceful and entertaining

Philadelphia dealer. According to Breen’s half cent encyclopedia, Forman

acquired the coin from another local Philadelphia dealer, C.J. Dochkus, who

obtained it from Philip “Piggy” Ward. Ward, best known as a buyer and seller of

stamps at the time, has come down through numismatic history as the man who was

able to purchase the coin collection of the University of Pennsylvania in the

early 1960s, for him a great coup.

That collection was

composed of two 19th century cabinets of incredible importance, both assembled

by wealthy Philadelphians. One was gathered by Robert Coleman Hall Brock, whose

collecting heyday extended from the mid 1880s to the late 1890s. The other was

built by Jacob Giles Morris, a pioneering numismatist who died in 1854. While

the coins traced back to Forman, Dochkus, and Ward uniformly come from the

University of Pennsylvania, numismatists have too often confused the Morris and

Brock collections despite the fact that each tells a fascinating story.

Robert Coleman Hall Brock

was a wealthy Philadelphia lawyer, collector, and philanthropist. Born in 1861,

he graduated from St. Paul’s School at 19 and continued his education at

Oxford. His passport application described him at 23 as 5’10”, with brown hair,

a high forehead, a large nose, and grey eyes. He apparently looked much the

same when he died in 1906, at the age of 45. Brock’s own father, John Penn

Brock, was the last in a line of John Brocks that extended back to the one who

immigrated to Philadelphia before 1684. When the father died in 1881, his

obituary described “immense coal and iron estates” that gave the surviving

generations access to education, travel, summer homes, and all the coins a

gentleman could acquire. Robert Brock collected heartily, acquiring enough

stamps to be called “one of the wealthiest and best known of American philatelists”

in 1894.

Brock’s interest in

collecting seems to have come and gone quickly. He was 33 when he sold his

stamps. At the age of 37, he not only donated his collection of coins to the

University of Pennsylvania, but also acquired large groups of ancient and

Islamic coins specifically to round out his donation. For his remaining days,

Brock gambled in Monte Carlo, became one of the first people to drive by

automobile from coast to coast in 1903, and was active in Philadelphia high

society.

In September 1898, an

article in Appletons’ Popular Science Monthly, a predecessor publication

of the modern Popular Science, ran an extensive article on the recently donated

Brock coins, focusing on his territorial and pioneer gold and highlighting that

his coins “are in excellent preservation.” Were an inventory of the Brock

cabinet discovered or somehow reconstructed, it would undoubtedly be an

extremely impressive assemblage. However, he appears to have been more of a

trophy hunter than a systematic collector. Today in 2017 this is a familiar

method, but generations ago the plan was to acquire one of each major variety.

Indeed, D. Brent Pogue did this in modern times with most of his series. For

example, his collection of $10 gold eagles of the 1795 to 1804 years, offered

by us in Part II, had marvelous specimens of each variety listed in A Guide

Book of United States Coins.

In 1900, just two years

after the Brock bequest, the University of Pennsylvania was given the coin

collection of Jacob Giles Morris. Morris was also the son of a wealthy old-time

Philadelphia family whose life ended at a tragically young age; he was just 54

when he was lost aboard the S.S. Arctic off Newfoundland in September

1854.

Morris was a pioneering

collector, with close ties to the Philadelphia Mint and the tiny community of

numismatic diehards that treated it as a clubhouse. Morris was actively collecting

as early as 1839. In 1851, he won lots at the auction of the Dr. Lewis Roper

Collection. On January 12, 1852, Morris paid a visit to Joseph J. Mickley to

play show and tell with his newly acquired 1792 Silver Center cent, and he

visited Mickley several more times over the course of the year. In 1852, Morris

also spent a considerable amount of time at the Philadelphia Mint; on November

21, 1851, Chief Coiner Franklin Peale announced that Morris would be placed in

charge of arranging the Mint’s own cabinet. It is nearly impossible to imagine

a scenario where Morris would not end up with an 1852 Proof set in his

collection.

William E. DuBois, the

assistant assayer who served as the longtime keeper of the Mint cabinet,

recalled in 1872 that there were four major collectors in Philadelphia 30 years

earlier: Joseph Mickley, Lewis Roper, Jacob Giles Morris, and himself. In 1843,

Morris was the second collector he mentioned in a letter to Matthew A.

Stickney, who had inquired about others who shared his passion. Mickley and

Morris apparently became good friends, both enjoying similar access to the

Mint’s employees, cabinet, and new issues. It is interesting to note that

Mickley’s collection, sold in 1867, included a six-piece 1852 Proof set. Lot

1721 brought $65 to Lilliendahl, more than any other Proof set in Mickley’s

collection. Auction cataloger W. Elliot Woodward noted, “I believe that a Proof

set [of this year] has never been offered before.”

After the death of R.C.H.

Brock in 1906, the University of Pennsylvania coin collection was sold, piece-by-piece.

It has been assumed for years that a portion of the Brock Collection was sold

to J.P. Morgan, deposited at the American Museum of Natural History in New York

in 1902, then transferred to the American Numismatic Society in April 1908.

This appears to have first been rendered in print in the 1958 ANS Centennial

History, but the timing makes it impossible. An April 8, 1908, New York

Times article states that the coins had been on display since 1902 and that

“the collection was originally brought together by a well-known Philadelphia

numismatist, and upon his death was offered for sale.”

The latest coin in the

Morgan bequest is dated 1901. This precludes the coins having belonged to Brock

who died in 1906 and who stopped collecting in 1898, the year his coins were

donated to the University of Pennsylvania. Instead, as recent inquiry by John

Dannreuther has determined, the J.P. Morgan coins at ANS were almost certainly

the property of Philadelphia dealer J. Colvin Randall, who died in 1901 and who

was the purchaser of record at the last known auction appearance of many of the

coins in the bequest. Randall, by the way, was a pioneer in describing early

American silver and gold coins by die varieties.

Though the University of

Pennsylvania appears to have kept many of Brock’s ancient and Islamic coins to

the present day, the United States coins were apparently deemed extraneous to

the museum’s mission and were deaccessioned. Edgar H. Adams noted in the

September/October 1908 issue of The Numismatist that all of Brock’s

coins were bequeathed to the University of Pennsylvania, thus every coin with

an authentic Brock provenance would have to be also ex. University of

Pennsylvania. However, not every coin that came from the University of

Pennsylvania has a Brock provenance. By the time the deaccessions began, it’s

clear the Brock coins and the Jacob Giles Morris coins had long since been

intermingled.

The first publicly

identified group of coins from the Brock and Jacob Giles Morris collections

were acquired by B. Max Mehl in 1952, an acquisition trumpeted by Mehl in the

January 1953 issue of The Numismatist and dispersed by private treaty

and auction in the years thereafter. John J. Ford, Jr. related to Dave Bowers

that around this time he went to Fort Worth and made a successful offer to Mehl

for the countless tokens and medals that he had accumulated over a long period

of years—such “exonumia” being beyond Mehl’s interest or knowledge.

Tradition also has it

that a group of Brock coins was sold by the University of Pennsylvania in the

late 1950s or early 1960s to the aforementioned Phillip “Piggy” Ward, a local

stamp dealer, on to dealer C.J. Dochkus, thence to Harry Forman of Philadelphia

before further dispersal. That provenance chain was given for this coin in the

Norweb sale, but it is unclear what precisely Ward and Dochkus handled.

(Interestingly, an 1852 Original Proof silver dollar from this group also

appeared in the Norweb Collection, perhaps from the same original set as this

coin.)

Letters preserved between

Dochkus and Eric P. Newman, who acquired the Jacob Giles Morris set of Sommer

Islands coinage, reveal the Morris connection. When Newman inquired of the

source Dochkus had located for world-class coins (coins well beyond those he

typically dealt in), Dochkus reported that they came from the “Miller

Collection.” The donor of the Jacob Giles Morris coins to the University of

Pennsylvania in 1900, as noted in Joel Orosz’s May 2002 article in The

Numismatist, was a descendant named Mrs. William Henry Miller, also known

as Sarah Wistar Pennock Miller, Jacob Giles Morris’ niece.

There appear to be just

four examples of this rarity known, of which the present specimen is the

finest, followed by the Eliasberg and Brobston specimens. A worn example

brought $32 in the 1924 F.R. Alvord sale, an enormous sum for a circulated half

cent, and last sold two decades ago in a Craig Whitford sale. Breen’s

contention that one was in the James A. Stack Estate did not prove true. When the

John G. Mills Collection was offered in 1904, Henry Chapman wrote that just two

examples were known, but it is unclear exactly which two he knew of at the

time.

This coin has been at the

center of a scholarly debate for a dozen decades, as various writers and

researchers have speculated about the true nature of the 1852 Large Berries

Proofs on the basis of precious little evidence. Neither Roger S. Cohen, Jr.

nor Walter Breen could get over the fact that the Large Berries reverse was

used for all Proofs from 1840 to 1849, then shelved until the production of

this coin. We now know, thanks to the assembly of the Phil Kaufman Collection

and follow-up research by John Dannreuther, that Proofs of each denomination

used a single dedicated Proof reverse for all of the 1840s and, in some cases,

as late as 1854, unless cracked or otherwise disabled. What Breen and others

condemned as out of order, under further examination, has turned out to have

been standard operating procedure.

Even before the status of

the 1852 Large Berries Proof half cent as an original striking or a later

restrike was clear, it was known as the prime rarity in the entire Proof half

cent series. This is finest known of them, making this perhaps the most

important post-1811 half cent extant.

Here is the provenance or

pedigree, to the best of our knowledge:

Probably from the Jacob Giles Morris

Collection, before 1854, then to Caroline W. Pennock, by descent; Col. Robert

C.H. Brock Collection, before 1898; University of Pennsylvania, by gift, ca. 1898;

Philip H. Ward, Jr. to C.J. Dochkus to Harry J. Forman; R.L. Miles, Jr.

Collection; Stack’s sale of the R.L. Miles, Jr. Collection, April 1969, lot 69;

Q. David Bowers; Spink & Son, Ltd.; Emery May Norweb Collection; R. Henry

Norweb, Jr., by descent, March 1984; Bowers and Merena’s sale of the Norweb

Collection, Part I, October 1987, lot 128; Jim McGuigan; R. Tettenhorst

Collection, by trade, October 1987; Eric P. Newman Numismatic Education

Society; Missouri Cabinet Collection (Eric P. Newman and R. Tettenhorst); Ira

and Larry Goldberg Auctioneers’ sale of the Missouri Cabinet Collection of U.S.

Half Cents, January 2014, lot 204.