I have loved Civil War tokens ever since I first read about them in the early 1950s. In 1958 I visited with George J. Fuld and his family at their residence in Wakefield, Massachusetts. George was the leading research on CWT, joined by his father Melvin, who lived in Baltimore. A few years later George developed the Fuld numbering system that remains the standard today, as in U.S. Civil War Store Cards, 3rd edition, edited by John Ostendorf, released by the Civil War Token Society in 2015 and U.S. Patriotic Civil War Tokens, 6th edition, edited by Susan Trask, just released—my copy is on its way as I write this. If you’d like either, see the CWTS website.

At age 79 I have been selling quite a few things from my collections of coins, tokens, medals, and paper money. My bank vault still has a lot of things, but quite a few have gone. I have been a consignor to every Stack’s Bowers Galleries auction in recent times, including the one just concluded in Baltimore. In addition, I have prepared a list of CWT for private sale.

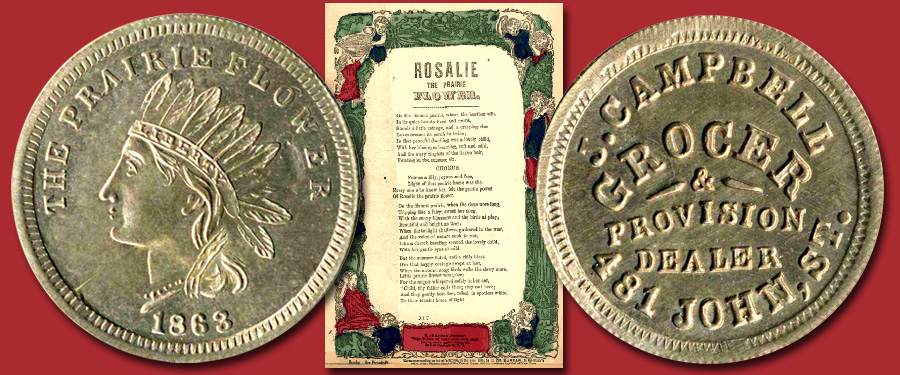

I have not stopped collecting, and my collection of obsolete paper money of New Hampshire, 1790s to 1866, is still growing, note by note. The other day I acquired a previously unlisted bill from the Belknap County Bank of Meredith. For Civil War tokens I continue to look for one of my favorites—the 1863 Indian Head with THE PRAIRIE FLOWER lettered on the obverse. I now have several dozen different examples.

Produced by John Stanton, well-known Cincinnati die sinker, engraver, and token manufacturer, several varieties of these pieces once circulated extensively, bearing on one side an advertisement or trade notice and on the other side the Prairie Flower, an Indian maiden whose features were borrowed from the federal cent first struck for circulation in 1859.

Virtually at its inception in 1863, John Stanton’s appealing Prairie Flower motif captured the imagination of numismatists, with the result that a number of delicacies were created, notable rare strikings in copper-nickel. Stanton took many advertising dies on hand for the tokens of Cincinnati merchants and other tradesmen and combined those dies with the Prairie Flower obverse.

The appeal of Stanton’s tokens endured, with The Prairie Flower being among the more popular designs.

It seems that this Indian maiden was already well-known by 1863. In Cincinnati and St. Louis in 1849, Emerson Bennett’s novel, The Prairie Flower, was published by Stratton & Barnard. In 1850, a revised edition was issued in Cincinnati by U.P. James. From the latter, we read of two frontiersmen on the prairie, who encounter an Indian maiden known as the Prairie Flower, seemingly a direct inspiration for Stanton’s token:

"Stand back! stand back! She comes! she comes!" I heard whispered on all sides of me.

"Look, Frank—look!" said Huntly, in a suppressed voice, clutching my arm nervously.

I did look; and what I beheld I feel myself incompetent to describe and do the subject justice. Before me, perfectly erect, her tiny feet scarce seeming to touch the ground she trod, was a being which required no great stretch of imagination to fancy just dropped from some celestial sphere. She was a little above medium in stature, as straight as an arrow, and with a form as symmetrical and faultless as a Venus. Twenty summers (I could not realize she had ever seen a winter) had molded her features into what I may term a classic beauty, as if chiseled from marble by the hand of a master. Her skin was dark, but not more so than a Creole’s, and with nothing of the brownish or reddish hue of the native Indian. It was beautifully clear too, and apparently of a velvet-like softness. Her hair was a glossy black, and her hazel eyes were large and lustrous, fringed with long lashes, and arched by fine, penciled brows.

Her profile was straight from forehead to chin, and her full face oval, lighted with a soul of feeling, fire and intelligence. A well formed mouth, guarded by two plump lips, was adorned by a beautiful set of teeth, partially displayed when she spoke or smiled. A slightly aquiline nose gave an air of decision to the whole countenance, and rendered its otherwise almost too effeminate expression, noble, lofty and commanding.

Her costume was singular, and such as could not fail to attract universal attention. A scarlet waistcoat concealed a well developed bust, to which were attached short sleeves and skirts—the latter coming barely to the knees, something after the fashion of the short frock worn by the danseuse of the present day. These skirts were showily embroidered with wampum, and wampum belt passed around her waist, in which glittered a silver-mounted Spanish dirk. From the frock downward, leggins and moccasins beautifully wrought into various figures with beads, enclosed the legs and feet. A tiara of many colored feathers, to which were attached little bells that tinkled as she walked, surmounted the head; and a bracelet of pearls on either well rounded arm, with a necklace of the same material, completed her costume and ornaments.

With a proud carriage, and an unabashed look from her dark, eloquent eye, she advanced a few paces, glanced loftily around upon the surprised and admiring spectators, and then struck the palms of her hands together in rapid succession. In a moment her Indian pony came prancing to her side. With a single bound she vaulted into the saddle, and gracefully waving us a silent adieu, instantly vanished through the open gateway.

Rushing out of the fort, the excited crowd barely caught one more glimpse of her beautiful form, ere it became completely lost in the neighboring forest.

"Who is she? who can she be?" cried a dozen persons at once.

"Prairie Flower…."

Wait, there’s even more. In 1855 George F. Root’s song of the same title was published, adding a first name to the Prairie Flower:

Rosalie, the Prairie Flower

Verse I:

On the distant prairie, where the heather wild,

In its quiet beauty liv’d and smiled,

Stands a little cottage, and a creeping vine

Loves around its porch to twine.

In that peaceful dwelling was a lovely child,

With her blue eyes beaming soft and mild,

And the wavy ringlets of her flaxen hair,

Floating in the summer air.

The song continued for four more verses, each with a chorus. I will have to check YouTube to see if anyone has sung it in recent years.

Such connections as the above make collecting tokens a lot of fun!