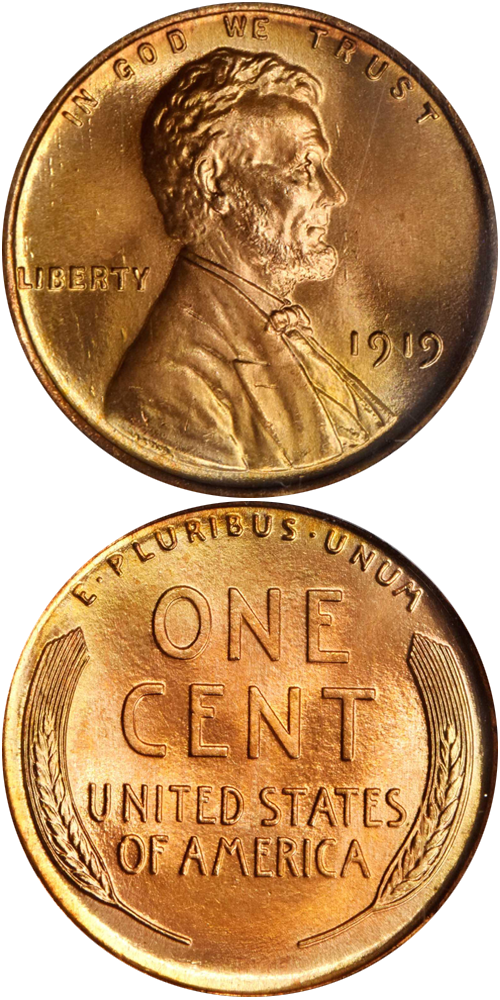

Designed by: Victor David Brenner

Issue Dates: 1909-1958

Composition: Bronze (1909-1942), New Alloy of 95% copper and 5% zinc (1947-1958)

Diameter: 19 mm

Weight: 3.11 grams (48 grains)

Edge: Plain

Business Strike Mintage: 19,552,500,823

Proof Mintage: 15,314 matte; 3,836,869 brilliant finish

After a brief coinage of Lincoln cents with V.D.B. initials on the reverse, the initials were removed, thus creating the "wreath reverse;' without initials, a style which remained in use through 1958. From 1909 through 1942, and again from 1948 through 1958, pieces were struck in the standard bronze alloy consisting of 0.95 part copper and 0.5 part tin and zinc. Separate types were created in 1943 with the zinc-coated steel and in 1944-1946 with a special alloy made from melted-down cartridge cases and which consisted of 0.95 part copper and 0.05 zinc; these last two types are discussed on following separate pages. It should be noted that the V.D.B. initials were put back on the Lincoln cent beginning in 1918, but this time they were of minute size and placed on Lincoln's shoulder. Generally, collectors do not consider the types with shoulder initials and without shoulder initials, or before 1918, and later, to be distinct types, although in a way they are.

Coined by the billions, cents of this type are common today, and no difficulty will be encountered in obtaining one in any grade desired from Good through superb Uncirculated, with the latter grade being the obvious choice. In addition, Matte Proofs are available from the 1909-1916 years and brilliant-finish Proofs are available of the 1936-1942 years and again from 1950 through 1958. Today, superb Matte Proofs are rare, while mirrorlike or brilliant Proofs of the later era are readily obtained.

Further Reading

In 1909, the 100th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln's birth, a new coin appeared on the American scene, the Lincoln cent. The designer was Victor David Brenner, whose initials appeared on the bottom of the reverse of the first issues. The obverse of the Lincoln cents shows the portrait of the president from the shoulder up, facing right. The reverse illustrates two stylized wheat stalks. This general format, with only minor variations, was produced from 1909 through 1958.

In 1909 much enthusiasm was generated for the forthcoming cent by various newspaper articles. The Mint received requests galore from banks, businesses, and others who wanted to have a supply of the new cents on hand. To anticipate the demand, 25 million were struck before distribution began on August 2nd. The popularity proved so great that Sub-Treasury outlets and banks rationed the new cents to a limit of 100 coins per customer. Long lines were formed at the payout windows of various Treasury Department outlets. On August 5th supplies ran out, and signs were posted reading, "NO MORE LINCOLN PENNIES." For the next few days newsboys, street sellers, and others had a field day selling the pieces for premiums. As usual in such instances, tales of scarcity helped fuel the demand. It was widely stated that there was a mistake in the design, and that all pieces would be recalled.

Following the introduction of the new cent, a design received favorably by numismatists, there were many public criticisms. The most curious of these was that the initials of Brenner, V.D.B., were too prominent. An advertisement for a private engraver (Brenner was an independent artist, not a Mint employee) should not appear on American coinage, it was said. Others proclaimed that the letters were too noticeable on the coin. Never mind that the initials of Augustus Saint-Gaudens, also an artist in the private sector, had been boldly emblazoned on double eagles ever since 1907, two years earlier. Consistency was not a virtue of the United States Mint or, for that matter, of the public. In response to complaints, the offending V.D.B. initials were removed, but not before 27,995,000 were struck at Philadelphia and 484,000 at San Francisco.

Although enough 1909 V.D.B. cents were produced to make them common for a half century later, the 1909-S V.D.B. produced in San Francisco quickly became a popular rarity. Almost from the outset a strong premium was attached to them. Beginning in the 1930s, when collecting Lincoln cents became a popular pastime with the public (inspired by the distribution of cardboard Whitman "penny boards" distributed in large quantities), the prized 1909-S V.D.B. was the object of desire by virtually every schoolboy bitten by the collecting bug. As such, the piece developed a cachet of its own. Other Lincoln cent issues might be rarer, especially in Uncirculated grade, but none is more famous.

During the first decade of production, Lincoln cents were struck at Philadelphia, Denver (beginning in 1911), and San Francisco. After the initial fever wore off, pieces were not saved in quantity. Today there are numerous issues, particularly among branch mint pieces of this era, which are quite elusive in Uncirculated grade. Worn specimens survive in approximate proportion to their original mintages.

Years ago, I bought from the owner of a prominent Pennsylvania newspaper what I thought was a complete set of Choice Uncirculated Lincoln cents from 1909 onward. However, upon inspection the 1915-D opening in the album was a duplicate 1915-S. Taking my trusty Guide Book in hand I was elated to find that 1915-D was a very common date. I anticipated that a letter or two sent to leading dealers would bring several quotations. A month later, not having found one, I telephoned several prominent dealers who advertised in the Numismatic Scrapbook Magazine, the leading periodical of the time. No luck! Finally, at a convention I was able to find the long-sought 1915-D. The price paid was not much, for the seller did not realize how rare the 1915-D was in that grade. Even today, this issue is listed at a curiously low price compared to other mintmarks of its time.

A rarity of the era is the 1914 Denver Mint issue. The 1914-D was minted to the extent of just 1,193,000 examples. In true Uncirculated grade the piece is rarer than even the relatively low mintage would suggest, and such pieces have always been highly prized. In the 1970s Mark Blackburn, a California dealer, told me he had purchased several rolls (each roll containing 50 pieces) of Uncirculated coins. I had the pleasure of examining several dozen of these, which were reddish brown in color with most original luster remaining. A roll or two of Uncirculated coins, part of the Harold MacIntosh estate, were distributed by the New Netherlands Coin Company in the 1950s.

On one occasion around 1971 or 1972 a California dealer telephoned me to say that he had a seller in his office who possessed a fabulous hoard of cents. Rare date Lincolns were offered by the hundreds, as were 1877 Indian cents. The pieces came, it was said, from an old hoard.

Jim Ruddy (my business associate at the time) and I hurried to examine the pieces. We quickly ascertained that something was wrong. Telling the owner of the pieces that we wanted to "study them," we requested that the pieces be left in our possession for a few hours. Upon his return we would most assuredly buy them, or so the owner thought. The Secret Service was called in, and we pointed out that these seemed to be modern fabrications. The various rare date coins all had the same coloration and surface characteristics. And, each had a peculiar tracery on the edge. Real coins separated in time would have developed many different shadings and would have displayed original differences in striking. As it turned out the Secret Service agent did not know the first thing about coins, common or rare. We dutifully explained the difference, but he was skeptical. When the seller returned, he was questioned briefly, and then he departed with his "rarities." Apparently, the matter was not completely forgotten, and the Secret Service later questioned the fellow in detail. They were told what seemed to me to be a fanciful tale: the pieces offered, which were priced at a fraction of catalogue value, were worn genuine specimens which had additional metal added to the surfaces by means of dental laboratory casting equipment. So, while the pieces were "treated" they were not counterfeit. This very clever explanation satisfied the government authorities, and the matter was dropped. Since then, I have often wondered how many of these pieces are in the hands of unsuspecting owners today.

In 1909 the Philadelphia Mint, following a procedure used by the Paris Mint for many years and a process used in Philadelphia for gold coins beginning in 1907, discarded the "brilliant" Proof format for the cent and instituted the Matte Proof style. Pieces of this method of manufacture displayed a grainy microscopically pebbled surface, without luster, which was said to "highlight" the design features. While such a proofing process might have been popular with French collectors, it certainly was not well received on this side of the Atlantic. Collectors were almost unanimous in their disapproval of the Proofs of this style made from 1909 through 1916. They preferred the mirrorlike finish of earlier years. As a result, most Matte Proof Lincoln cents simply sat on the shelves. Years later one of the Chapman brothers purchased a quantity of these from the Mint, selling them to William Pukall, a New Jersey dealer. Around 1954 and 1955 I bought large numbers of these, all in original Mint tissue paper, from Mr. Pukall. Even though they cost just a few dollars each at the time, they did not sell quickly. David Proskey, another old-time dealer, also purchased many unsold pieces from the Mint. Many of these later passed to Wayte Raymond.

In recent years the rarity of Matte Proof Lincoln cents (and other Matte Proof denominations) has been realized. Of the 1,365 Matte Proofs reported coined for 1914, for example, probably only a few hundred still survive. Unless they have been cleaned, Matte Proofs of this era nearly always show various gradations of brown, gold, and iridescent toning, due to the chemical composition of the tissue paper in which they were distributed and stored.

One of my favorite recollections concerning Lincoln cents of the first decade of production concerns a situation which happened around 1960. At a sale held by the New Netherlands Coin Company in New York City, a 1915 Lincoln cent, a coin which at the time was no more significant price-wise, or at least not much more, than cents of 1913 and 1914 (to mention just two examples) appeared in an auction sale. Apparently, there was confusion when the lot came up and the coin sold for several times the current valuation.

I remember gasps and muted conversations in the audience. Everyone wondered what happened. Here was an ostensibly common inexpensive coin that two experienced collectors were enthusiastically competing for. Perhaps they knew some "secret" not disclosed to the rest of the audience. It later developed that both bidders believed that they were competing for a different lot. As the error was not discovered until later and was not announced at the sale, the new auction record was accepted as gospel by those who read about it, and before long the price of all 1915 Lincoln cents in Uncirculated grade had risen sharply! All of the sudden 1915 became much more expensive than 1913, 1914, and its other contemporaries.

A year or two later I purchased a quantity of rolls of early Philadelphia Mint Lincoln cents from an Endicott, New York estate. As might be expected, there were just as many 1915 cents in the group as there were as 1910, 1911, and other issues. When I advertised the pieces, I found that the 1915s sold much better, for everyone considered them to be rarities.

Lincoln cents struck at the Denver Mint through the late 1920s more often than not are very weakly struck. Most pieces have light definition of the details on Lincoln's portrait on the obverse and on the wheat stalks and other features of the reverse. Actually, the term weakly struck is not appropriate, for the coinage presses exerted sufficient pressure to bring the design details up properly. The problem was in die spacing. The closer the dies are spaced together during the coining process, the sharper the details will be, for the metal in the planchet is forced up into the deepest recesses of the dies. At the same time, this extra metal movement causes faster die wear, necessitating more frequent replacement. Spacing the dies wider apart reduces wear, but at the same time many details are weakly impressed. The term "weak strike" is commonly used by numismatists to denote this.

One of the most curious Lincoln cents of the 1920s is related to this situation: the so-called 1922 "plain" variety. This piece is simply a defective 1922-D struck so weakly that the D mintmark is not visible. Indeed, some specimens show the obverse features and the reverse wheat stalks simply as outlines with few details. An Uncirculated coin may have no more detail than what normally one would expect on a Very Good grade piece which had been worn for many years! However, unlike most weakly struck coins (which sell at sharp discounts from regular prices), the 1922 "plain" sells for an immense increment, much more than a perfect 1922-D coin. Here is a really peculiar situation. I am not the arbiter of what something should be worth and what should be collected, and there is no question that the 1922 "plain" is at least interesting. However, whether it should be a landmark "rarity" worthy of selling for a very high price in comparison to a perfectly struck coin seems at least to me to be questionable. In any other series, Liberty Standing quarters and Liberty Walking half dollars being examples, weakly struck pieces would bring less, not more, than sharply struck ones. However, the 1922 "plain" is a part of numismatic tradition.

Lincoln cents of the 1920s exist in approximate proportion to the original mintages, so far as worn pieces go. Uncirculated specimens survive as a matter of chance. In general, Philadelphia Mint pieces are far more common than their Denver or San Francisco Mint counterparts. Sharply struck Denver coins are for the most part quite rare, particularly among earlier issues of the decade.

The Depression began in late 1929. By the early 1930s it was well underway. As a result of nationwide banking and financial difficulties, the call for new coinage was lessened. Mintages were reduced, and in particular at the San Francisco Mint in 1931 a relatively small quantity of cents left the coining presses, just 866,000 examples, the only issue since the 1909-S V.D.B. to register a total of less than a million. There were enough sharp collectors and dealers around that 1931-S cents were acquired in substantial quantities. The 1931-S later became scarce in circulation due to the low mintage. The demand for worn pieces, engendered by the Whitman penny boards, quickly made it a sought-after issue, placing an additional pressure on the supply of Uncirculated pieces. Today, while the 1931-S in Uncirculated grade is easier to find than the 1931-D (of which about five times as many were minted), still there is a ready market due to its rarity in lesser grades.

Although issues of 1930 through 1933 were saved in fairly large quantities, it was not until around 1934 that coin collecting caught on in a big way with the public. Almost all regular date and mintmark varieties of United States coins after 1934 are known in bag quantities, with the 1936-D quarter possibly being the single exception to this observation. As the demand for individual pieces increased, and coins developed high values when offered on a single basis, rolls and bags were widely dispersed. Today, bags of any coin dated before 1950 are unusual.

In 1934 and 1935 coin collecting became a popular national pastime. Wayte Raymond's Standard Catalogue of United States Coins was launched, thus providing changing market price information. The Numismatic Scrapbook Magazine, published by Lee and Cliff Hewitt in Chicago, began. Published on a monthly basis, it gave The Numismatist, the official journal of the American Numismatic Association, a run for its money and quickly captured the lion's share of advertisers, due mainly to its livelier editorial content. Commemorative half dollars became a fad, and the profits derived from them made news headlines, drawing still more people to coins, some of whom investigated and collected Lincoln cents.

In 1934, 219,080,000 Lincoln cents were struck, a record high number for the era. This high mintage, in combination with the collecting factors just observed, resulted in Lincoln cents from 1934 onward being much more plentiful than those of earlier years. Today, Lincoln cents with the wheat reverse dated in the 1934-1958 years are available inexpensively. As time moves on and coins get older, more of them are cleaned, more are mishandled, and in general earlier pieces become harder and harder to find. One cannot "automatically" obtain a set of sparkling Choice brilliant Uncirculated Lincoln cents from 1934 onward simply by walking into a local coin shop, as one once could. Today some issues of the 1930s, while not expensive, may require some hunting.

In 1955 a curious error occurred at the Philadelphia Mint. One working die obverse was struck twice by the master die. The second striking was in a slightly different alignment, with the result that the obverse of pieces struck from this die appeared to read: IINN GGOODD WWEE TTRRUUSSTT. The word LIBERTY and the 1955 date were likewise doubled. First appearing in circulation in the Binghamton, New York area and in Massachusetts, these pieces captured the attention of sharp-eyed collectors. Numismatic News was the first to publish the variety, if memory serves, calling it the 1955 "shift" cent. At the time of issue pieces were traded among collectors in the Upstate New York area for 25c each! As time went on, the variety became popular with collectors. The price rose to $1, then to $5, on past $7, to $10, and even beyond. Robert Bashlow, a New York City dealer who had a penchant for unusual things, visited my office (then located in New York) and bought all I had. To replenish my stock, I had to pay in some instances more than I had just sold pieces for!

Research and interviews with Mint employees later revealed that on one particular day in 1955 several presses were coining cents. Production of each press went into a common box where the pieces were mixed together. Late in the afternoon a Mint inspector noticed the bizarre doubled cents and removed the offending die. By that time more than 40,000 pieces had been produced, about 24,000 of which had been mixed with normal cents. The decision was made to destroy the cents that were still near the press but not to disturb those mixed with others. No one at the Mint dreamed that numismatists would ever notice the variety! The demand for the 1955 error, which became known as the Doubled Die, increased, particularly when it achieved a listing in the most popular of all numismatic reference books, A Guide Book of United States Coins.

Throughout the Lincoln cent series, a number of interesting variations have been collected to one degree or another. Some of these were unknown to numismatists until recent years when examining coins under high power magnification became a popular pastime. Included are variants such as the 1909-S Lincoln cent with the S over a previous erroneous horizontal S, and the curious 1944-D with the mintmark over an earlier S. Both of these varieties seem to be great rarities, but as of the present writing they are not particularly high-priced, and openings for them are not included in popular albums.

In a class by itself is the 1943 zinc-coated steel cent. During the height of World War II copper was in short supply due to the military effort. In 1942 experiments were made in an effort to seek an acceptable substitute for the scarce metal. At the Philadelphia Mint and at the Hooker Chemical Company (North Tonawanda, New York) impressions from special dies (medal dies made for the purpose) were produced in fiber, zinc, and other substances.

In the following year, 1943, zinc-coated steel was adopted as the standard, and more than a billion Lincoln cents were produced in this format at the three mints. A few leftover bronze planchets from the previous year found their way into the coining process, with the result that a number of 1943 bronze Lincoln cents are known. Years ago, these achieved great publicity. It was said, for example, that Henry Ford would deliver a new automobile in exchange for such a piece. During a later era, the 1960s and 1970s, several 1943 copper cents crossed the auction block or were offered privately and sold in the range of a few thousand dollars up to close to the $10,000 level, thus establishing a valuation. In more recent times, prices well in to six-figures were achieved, with several selling in excess of $1 million.

From 1944 through 1946 used cartridge cases were melted down and cent planchets were made from them. Inevitably a few of the earlier zinc-coated steel planchets found their way into coining presses early in 1944, producing incorrect metal strikings somewhat related to the 1943 copper issues. 1944 steel cents have come on the market a number of times and have attracted attention among specialists.