One of the results of the Civil War, was the widespread hoarding of virtually all hard metal coinage. Silver and gold coins were particularly vulnerable, and by 1863-64, virtually all of these coins had disappeared from circulation. The U.S. mint began the conversion to base metal coinage, and in 1865 introduced a three-cent coin made of 75% copper and 25% nickel, and the following year, a five-cent coin of the same alloy was introduced. These five-cent coins effectively replaced the silver half dime, although the half dime would continue to be minted in limited quantities through 1873.

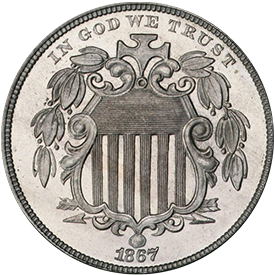

The first motif for the five-cent nickel (designed by James B. Longacre) featured a large shield, similar to that used on his two-cent bronze coin of 1864. On the reverse was the large numeral 5, surrounded by stars and rays between the stars. Due to striking difficulties, the rays were removed mid-way through 1867, and the design then continued unchanged through 1883 when it was replaced by the Liberty Head or “V” nickel.

Further Reading

Nickel alloy five-cent pieces of the shield design first made their appearance in 1866. However, as a prelude to this, many different types of pattern coins were issued during the previous year, 1865, and earlier during the same year, 1866.

In the study of almost all coin denominations, patterns furnish an insight to "what might have been." It is often the case that many different designs, some quite artistically superior to those finally adopted, were tried before a particular style was first issued. In my opinion, the studies of pattern coins and regular issues are inseparable.

Early nickel five-cent piece patterns were made in many different styles. Among the most interesting are those with the portrait of President George Washington and other issues, rarities today, depicting President Abraham Lincoln.

The Shield nickel design as finally adopted is more of a geometric design than an artistic design. The devices are symmetrical on both sides, and there is little to recommend the piece as a work of art. It is more or less a copy of the shield on the two-cent piece issued two years earlier. It seems to me that perhaps either the Washington or the Lincoln design would have been more interesting.

The first Shield nickel design regularly issued was the type with rays released in 1866. The obverse features the shield design, and the reverse depicts a circle of stars with radiant stripes or rays between them. Today collectors refer to this design as the "with rays" type, but 60 or 70 years ago this motif was designated as the "stars and bars" design in coin catalogues. The latter terminology has been largely forgotten today.

The term “nickel” came into use to designate this type of five-cent piece. As the composition is 75% copper and 25% nickel, the term copper would have been more appropriate. However, the relatively small amount of nickel gives the alloy a bright silver appearance, like nickel metal, so the term nickel stuck.

The initial year, 1866, saw a mintage of 14,742,500 pieces, with perhaps the tag-end 600 issued as Proofs. The type quickly caught on, and before long nickels were a staple in the channels of commerce, circulating alongside fractional currency notes, Indian cents, two-cent pieces, and nickel three-cent pieces. Silver coins were nowhere to be seen. Indeed, it was not until the mid-1870s that specie (coin) payments were resumed by the government, and Liberty Seated half dimes, quarters, and other issues were clinking in cash boxes.

The presence of rays or bars on the shield nickel caused some striking problems related to metal movement, so early in the year 1867, after 2,019,000 had been struck with the rays-type reverse, the rays were discontinued. Later in the year 28,890,500 of the new format were produced, thus isolating the 1867 with-rays nickel as a rare issue by comparison.

From the very outset problems with striking surfaced. The hard alloy caused rapid die wear. Metal movement was a problem. To prolong the life of dies and to facilitate striking, the obverse and reverse dies on the coining presses were spaced slightly farther apart than they might have otherwise been, with the result that light impressions characterize the majority of business strikes seen today. The die wear caused numerous breaks. With magnifying glass in hand, the interested numismatist can detect myriad traceries of breaks, usually along the border, on numerous early shield nickel issues. 1866 and 1867 seem to be particularly outstanding in this regard. To prolong their life, dies, once they became worn, were sometimes repunched in their entirety, but more often simply the date numerals were strengthened. This practice gave rise to many different varieties of date recuttings, again a situation particularly prevalent during the first few years of issue. For one die, the recutting was accomplished by severely misaligning the second set of 1867 numerals, thus creating a sharply doubled date. Another variety, this one of 1866, has a "ghost" earlier numeral 6, from a previous use of the die, visible after the regular 1866 date, giving the fanciful appearance of “18666”.

Type set collectors have created an exceptional demand for pieces of the 1866 and 1867 type with-rays, with the result that these pieces, while not necessarily rarer than certain later dates, have commanded strong prices. The 1867 with-rays is a rarity, or at least a scarcity, on its own, but as most demand is from type set collectors, not date set collectors, in recent years the prices have become nearly identical. The market difference between an 1866 and an 1867 is very small.

The effect that type set collecting has had on the prices of certain early coins can be shown by many different examples. Illustrations pervade virtually every series. In brief, years ago, particularly before 1960 when type set collecting became popular, it did not make a great deal of difference whether an early design was short-lived or made for a long period of years. The basic or absolute rarity of the coin was more important. Whether it was rare as a type was not a major consideration. After 1960, when few numismatists could afford to collect "one of everything," figuratively speaking, type collecting became prominent. Suddenly, numismatists who were not collecting quarter dollars by dates wanted a 1796, simply because it was needed to illustrate the Draped Bust obverse and Small Eagle reverse, for this style was minted only in this single year. Rare dates diminished in importance. It was type that counted.

An interesting illustration of this is afforded by listings in A Guide Book of United States Coins. The 1954-1955 edition priced a Fine 1866 Shield nickel at $4 and an 1867 with-rays nickel in the same grade at $18. In other words, the 1867 with rays, being much rarer (about seven times rarer from mintage viewpoint), sold for 4½ times as much. Back then the demand was for pieces as dates.

By contrast, the 1985 edition of the same publication priced a Fine 1866 at $20 and a Fine 1867 for $29, while a more recent (2022) edition priced them at $60 and $75 respectively, or only 25% more. A beneficial result of the present type set oriented market is that a collector with an eye to acquiring rarities can often obtain lower mintage or rarer issues at only slightly more than common ones, a sharp contrast to the situation faced by numismatists years ago. In a 1984 offering an 1882 Shield nickel in Choice Uncirculated grade was priced just ten percent less than a similarly-preserved 1871, although the 1871 is at least 50 times rarer!

From the standpoint of availability today, nickels of the 1866 and 1867 with-rays design can be obtained in all grades from Good through Uncirculated. In the latter grade 1867 with-rays is particularly elusive. Most pieces seen, particularly those dated 1866, are softly struck. Pieces with needle-sharp details are exceedingly elusive.

Proofs of 1866 are fairly scarce and may have been minted just to the extent of about 600 pieces (although the exact quantity has never been reported). Apparently sets sold to collectors early in the year, before the Shield nickel was introduced, lacked these coins. Today they are considered to be important issues. Proofs of the 1867 with rays are among the greatest of all American Proof rarities. Fewer than 20 are believed to exist.

The second design type in the Shield nickel series is furnished by the without-rays style made from 1867 through 1883. Mintage was continuous throughout this span. Business strikes of several dates can be considered scarce, notably 1871 and, in particular, 1879 through 1881. Also elusive are two Proof-only issues, 1877 and 1878. In those two years no business strikes were produced.

Nearly all 1878 Proof nickels have a generous degree of "Uncirculated mint frost." In other words, they have lustrous, frosty surf aces like a business strike. Many show no traces of Proof surface whatever! It is an interesting debate whether pieces should be called Proofs because they were made that way by the Mint and sold as Proofs to collectors, or whether they should be called Uncirculated, for they appear to be in the latter grade. Tradition dictates the Proof classification.

In Uncirculated grade, the most often seen date among Shield nickels of the 1867-1883 without-rays type is the 1882, which also happens to be the highest mintage issue among later pieces. The frequency of circulated Shield nickels, from worn smooth through AU, is approximately proportional to the mintages, with 1867, 1868, and 1869 showing up especially often.

Proofs of later years in the series are readily available, although key dates such as 1877 and 1878 (Proof-only issues as no examples were made for circulation), and 1879 through 1881 tend to be more expensive. The latter years are not particularly rare in Proof grade, but business strikes are elusive, thus creating an additional demand for the Proofs.