Contrary to popular belief, the California Gold Rush was not the United States’ first gold rush. That honor belongs to the Carolina Gold Rush that had its origins in the discovery of a large gold nugget in North Carolina in 1799. Mining began in earnest in the region in the earliest years of the 19th century and continued for several decades.

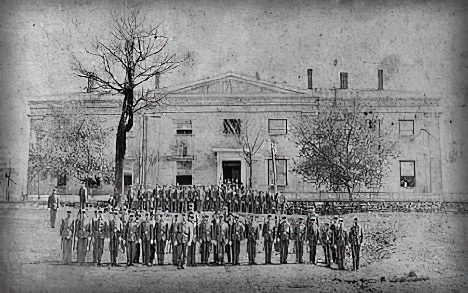

The Dahlonega, Georgia Mint.

This early event was overshadowed by the nation’s second gold rush, the Georgia Gold Rush, sparked by discoveries in 1828 in a region that is now part of Lumpkin County. Additional finds were made in the mountains of North Georgia, and soon miners from North Carolina were drawn to the new area. The heyday of the Georgia Gold Rush ended in the early 1840s, by which time gold was becoming increasingly difficult to find in the region. The experiences of mining gold in North Carolina and Georgia during the early decades of the 19th century, and the skills acquired through those experiences, created a population of Americans who were eager and able to travel west and participate in what proved to be the more extensive -- and consequently more famous -- California Gold Rush of the late 1840s and 1850s.

The Founding of Dahlonega, Georgia

Native Americans living in what is now Georgia had shared reports of gold with European explorers as early as the 16th century. Even so, the “discovery” of gold in the region is dated to 1828, although under exactly what circumstances is not known. Some accounts credit Benjamin Parks, who supposedly found gold on his birthday that year while walking along a deer path. There are several other accounts for the “discovery,” although none are supported by contemporary documentation. Regardless, by 1829 the Georgia Gold Rush began in Lumpkin County, as evidenced by this account published in the August 1, 1829, edition of the Georgia Journal:

GOLD.—A gentleman of the first respectability in Habersham county, writes us thus under date of 22d July: ‘Two gold mines have just been discovered in this county, and preparations are making to bring these hidden treasures of the earth to use.’ So it appears that what we long anticipated has come to pass at last, namely, that the gold region of North and South Carolina, would be found to extend into Georgia.

An influx of miners resulted in the original small settlement in the area of present-day Dahlonega rapidly expanding into a booming mining town. The Georgia General Assembly named the town Talonega on December 21, 1833, changing it to the now-familiar Dahlonega on December 25, 1837, after the Cherokee word “dalonige” for “yellow” or “gold.”

The Dahlonega Mint and Its Coinage

Despite the dangerous and time-consuming process of transporting Georgia gold to the Philadelphia Mint for coinage, it was not until 10 years after the Gold Rush began that a branch of the United States Mint was opened in Dahlonega to service the region’s mining operations. In fact, were it not for wider political considerations the Dahlonega Mint could have been nothing more than a story of what might have been.

The origins of the Dahlonega Mint can really be traced to 1792, not 1828. The Act of April 2, 1792, which established the Mint and the nation’s coinage system, set the value of gold relative to silver at 15 to 1. This ratio undervalued gold and overvalued silver, preventing domestic circulation of gold and resulting in its widespread export during the early decades of U.S. Mint operations. By the 1820s, in fact, gold coins were entirely absent from domestic circulation with commerce conducted using an unstable combination of Spanish- American silver coins, bank notes and, to a lesser extent, U.S. copper and fractional silver coins. The first steps to remedy this problem were taken in 1830, although the process did not come to fruition until passage of the Act of June 28, 1834.

This significant Act was a victory for President Andrew Jackson’s hard money policy that sought to undermine bank notes in circulation in favor of gold coinage. It finally addressed the problem of the relative value of gold to silver in the United States by fixing the ratio at 16 to 1. This represented a last-minute change from a proposed ratio of 15.625 to 1, the impetus for which is thought to have come from two powerful special interests: Eastern businesses, which wanted gold restored to active circulation to aid in foreign trade, and Southern mining interests, which believed that the return of gold to circulation would create a large market for Carolina and Georgia bullion. The Act succeeded in its primary aim of returning gold to active circulation and, as anticipated, Southern miners were now faced with a sudden and dramatic increase in demand for their precious metal.

The Philadelphia Mint had been the primary destination for Georgia gold since 1828, and from 1830 to 1837 it received more than $1.7 million in deposits from that region. Calls for assay offices and, later, branch mints in North Carolina and Georgia had first been mooted in 1830, but after passage of the Act of June 28, 1834, Southern politicians finally had the clout they needed to secure establishment of these facilities. This was achieved through the Act of March 3, 1835, which created branch mints in Charlotte, Dahlonega and New Orleans, the first two solely for the processing and coining of gold.

Commissioner Ignatius Few purchased ten acres south of Dahlonega in August, 1835 and contracted with the architect Benjamin Towns to construct a mint facility within the next year and a half. Machinery consisting of cutting presses, a fly wheel, a drawing frame, a crank shaft, a coining press, and eighteen annealing pans was installed during 1837, and by early the following year, the Mint was ready to begin operations.

The Dahlonega Mint officially opened for business on February 12, 1838, with the first coins -- 80 half eagles – struck on April 21. The Mint would operate for 24 years, striking gold coins in dollar, quarter eagle, three-dollar and half eagle denominations. It is ironic that the first full decade of the Mint’s activities coincided with a sharp decline in gold mining in Georgia. Consequently, yearly mintages at Dahlonega were small throughout the 1840s. The facility did receive a temporary boost from 1850 to 1855 due to an influx of California gold. This source largely dried up after the first gold coins were struck at the newly established San Francisco Mint in 1854 and production at Dahlonega fell off markedly and remained very limited, especially compared to those of the West Coast facility. The outbreak of the Civil War in 1861 spelled the end of coinage operations at the Georgia mint.

Outraged over Lincoln’s victorious presidential campaign, the legislature of South Carolina voted to secede from the Union on December 20, 1860, initiating what would be a cascade of secessions over the following months. Georgia signed the Ordinance of Secession on January 19, 1861, becoming the fifth state to secede from the Union, although the Southern Confederacy did not officially assume control of the Dahlonega Mint until April 8, 1861.

While some of the remaining bullion was coined into gold dollars and half eagles under Confederate authority, the Mint served as merely a depository for the Confederate Treasury for the remainder of the Civil War. After the cessation of hostilities, the United States Treasury provided estimates for reinstating the facility as an assay office or mint, but neither option was adopted. In 1873, the building was given to the North Georgia Agricultural College. The original Dahlonega Mint building burned down in 1878, and a replacement structure (Price Memorial Hall) constructed on its foundation now serves as an administration building for the University of North Georgia.

Dahlonega Mint gold coinage as a group is scarce, and all issues are rare in the finer circulated and Mint State grades. Throughout its operational history the highest yearly mintage for an issue from this branch mint was achieved in 1843, when 98,452 half eagles were produced. Numerous Dahlonega issues have mintages of fewer than 10,000 coins, with several not even reaching 5,000. But mintages are only part of the story when it comes to understanding the scarcity of Dahlonega Mint gold. Almost without exception, these coins saw immediate and widespread commercial use that in most cases ended with destruction through melting.

The rarity of its coinage, combined with the appeal of the Antebellum South era, has made the Dahlonega Mint very popular with specialized gold collectors. Through its 1861-dated coinage the facility also has direct ties to the formation of the Southern Confederacy. Finally, the difficulty of locating well produced Dahlonega Mint coins at any grade level is a challenge that attracts advanced numismatists. Minting operations in the remote mining region of North Georgia during the late 1830s, 1840s and 1850s was difficult under the best of circumstances. External factors further complicated the process, such as the propensity of the engraving department in the Philadelphia Mint to send dies that were deemed unsuitable for use at the nation’s main coinage facility to the branch mint in Dahlonega.

The discovery of gold in California, the booming Gold Rush there during the 1850s, and the beginning of coinage operations at the San Francisco Mint in 1854 led to calls to close the Dahlonega facility. Mining in Georgia was already in decline by that time, and it suffered an even greater setback as people headed west to pursue more attractive prospects in California. As the Mint’s usefulness was increasingly called into question, it is not surprising that the worst produced Dahlonega Mint issues are those dated from the mid-1850s through cessation of coinage operations in 1861.