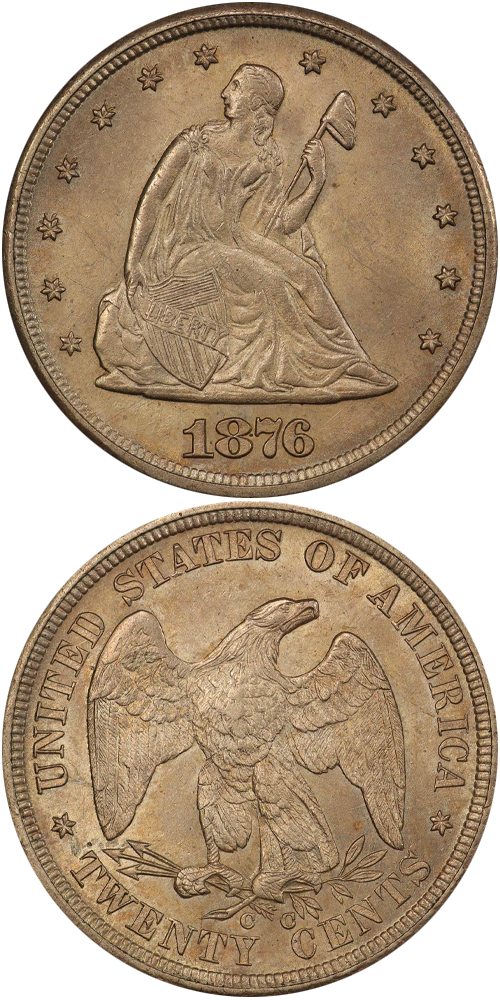

1876-CC Twenty Cent

The Carson City Mint employed only a single pair of dies to strike 10,000 twenty-cent pieces in 1876. The most prominent diagnostic of this die marriage is bold doubling to the word LIBERTY and stars 2 through 9 on the obverse. Patches of raised die lines are seen at Liberty's foot and at both sides of the date, and the top of an errant 8 is seen in the denticles below the primary digit 8 in the date. On the reverse, the mintmark is widely spaced with the first C centered over the letter Y in TWENTY and the second C centered over the extreme left edge of the letter C in CENTS. A faint vertical die line extends up from the left foot of the letter E in CENTS.

We have been fortunate enough over the years to present our "fair share" of 1876-CC twenty-cent pieces, including the magnificent MS-64 example from the Battle Born Collection, offered by us in 2012 at our annual ANA Auction, where the coin realized a full-bodied final price of $460,000. In the process of writing that catalog, Jeff Ambio, Rusty Goe and Q. David Bowers did an admirable job of describing both the coin and the history behind it, as well as the history of the denomination. We graciously reprint Rusty Goe's enlightening and definitive commentary herein, followed by Dave Bowers' numismatic reflections.

Rusty Goe: "The U.S. twenty-cent piece failed miserably as a newly introduced denomination in the mid-1870s, but one of its end products became the "Duke of Carson City coins."

How Should A New Nation Make Change?

Thomas Jefferson called it 'Money Arithmetic' when he wrote about the necessity of making it easy for the citizens of the newly formed United States of America to figure out how to make change. Robert Morris, the Superintendent of Finance in the new Confederation, warned in 1782 that money units should be denominated using a decimal system. He said this would make the new nation's money system easier for the masses to calculate. He wrote that, 'Whenever such things require much labor, time, and reflection the greater number who do not know are made the dupes of the lesser number who do.'

Thomas Jefferson, in his paper on American coinage, written about 1785, advocated Morris's decimal system. Jefferson's plan included a fifth of a dollar, which he said was equal to the old Spanish pistareen. By the time the U.S. Mint began to produce the country's first federally issued silver coins, components of a decimal system were fused with aspects of a binary system in which certain denominations were divisible by two, resulting in a 'mule coinage system, which would confound commerce for decades to come.

Could a Twenty-Cent Piece Harmonize the Mule Monetary System?

The challenge faced by government officials to keep sufficient quantities of money in circulation, to enforce standard weights and measures during volatile precious metals markets, and to ensure that citizens retained confidence in exchangeability rates presented many problems. No American wanted to be a 'dupe,' as Robert Morris had suggested in 1782, and get shortchanged.

By the early 1870s, grumblings echoed through the western states about the unfair practices experienced by patrons when paying for inexpensive purchases. In an article in the Daily Alta California on August 28, 1871, the writer described his dissatisfaction with one of California's customs of making change. He said merchants in the Pacific states priced low-cost items at twelve and a half cents -- a 'bit' in contemporary parlance. Since the only small denomination coins circulating out west were dimes, quarters, and half dollars, he found it difficult to pay for a twelve-and-a-half-cent item without getting cheated, or at best ridiculed. He declared, 'The whole system is clearly rotten from head to toe.'

In the November 24, 1871 edition of the Daily Alta, a staff writer announced that a petition had been sent to Congress 'to provide that no quarter dollar pieces shall be coined, that 'two-dime' pieces shall be substituted, and that the half dollar pieces all be called 'five-dime' [pieces].' And on December 13, 1871, that same newspaper reinforced the movement to introduce a twenty-cent piece. 'The reason we adhere to the term 'bit,' and the use of the imaginary twelve-and-a-half-cent coin, is that our Government, departing from its superior decimal divisions, starts us on the [Spanish-] Mexican system, by dividing the dollar into halves and quarters.' The writer urged that the U.S. government add a twenty-cent piece to its system, and abolish the quarter.

California, the most populated Western state, led the way in getting the proposed twenty-cent piece before leaders in Washington, DC. Its U.S. House delegate, Aaron A. Sargent, introduced a bill for a twenty-cent piece in January 1872. The Daily Alta on January 18, 1872, announced that at least 2,500 businessmen, leading officials, and capitalists, had signed a petition and forwarded it to Washington, DC, asking that the government substitute 'two-dime' pieces for two-bit pieces (quarters).

Legislation to pass the bill stalled. The catalyst needed to break through the logjam and get the new denomination into circulation came in the form of Nevada's freshman U.S. senator, John Percival Jones. Jones's close connections with Nevada's mining industry triggered rumors that his twenty-cent piece proposal was nothing more than a scheme to bolster the price of his friends' surplus supply of silver. Treasury Secretary John Sherman said long after Congress had rescinded the twenty-cent piece, that the coin only came into existence because Jones wanted to pay back Nevada's miners. Regardless, twenty-cent piece proposals had predated Jones's efforts, with notable agitation occurring in 1806 - 1807, the 1850s, and the early 1870s.

Senator Jones's bill found support but lingered in Congress through the rest of 1874. In December that year, Treasury Secretary Benjamin Bristow endorsed the coinage of 'double dimes,' but as the Daily Alta observed on December 18, 1874, the secretary 'does not say anything about the quarter dollar.' The newspaper's editorial staff firmly believed that the quarter 'should be cut off entirely, as not only unnecessary, but pernicious.'

Within months after President Ulysses S. Grant had signed the twenty-cent piece law into effect in March 1875, warning signals flared when citizens learned that the twenty-cent piece bill did not repeal the act to coin quarter dollars. It made no sense to many astute observers to have two coins circulate that differed in value by only 20 percent.

Dashed expectations led to cries of 'Failed Experiment' in newspapers across the country in the latter half of 1875. Western journalists stubbornly defended the much-maligned coin. Earlier in the year, the Los Angeles Herald (March 18, 1875) had reported 'We may soon expect an abatement of the 'bit' nuisance,' once twenty-cent pieces started to circulate. Reporters in other parts of the country claimed the twenty-cent piece could accomplish no more than could the use of two dimes.

On the last day of November 1875, the Daily Alta bemoaned the fact that 'some of the newspapers have hastily and unreasonably declared [the twenty-cent piece] a failure.' The Daily Alta blamed the unpopularity of the twenty-cent piece on the government, which it said, 'has not yet done its duty in the matter.' No one would use double-dimes, declared its columnist, until 'Congress should prohibit the striking of any more quarters.'

Despite the support expressed by its advocates, it became clear as January 1876 approached that the twenty-cent piece was a one-year wonder. The San Francisco Mint never issued another twenty-cent piece after 1875, and if not for the Philadelphia Mint's obligation to furnish examples for distribution at the Centennial Exposition held in that institution's home city in 1876, and its commitment to collectors to issue Proof examples, we would not have 1876 twenty-cent pieces from that mint today.

Even Director of the Mint Henry R. Linderman, who admitted several years later, that the twenty-cent piece 'is a convenient decimal division of the dollar and should have been originally authorized in place of the quarter-dollar piece' (Money and Legal Tender in the United States, Henry R. Linderman, 1879, G. P. Putnam's Sons, NY), said it was a failure.

The three operating mints produced 1,355,000 of these experimental coins before Congress repealed the twenty-cent piece act on May 2, 1878. All told, the government used 196,041.40 ounces of silver to make these unpopular coins. That total represents less than 10 percent of the monthly allocation for silver generated by the Bland-Allison Act, which introduced Morgan silver dollars to the nation's money supply. The production of twenty-cent pieces did not as some predicted it would reinforce a sluggish silver market; and it did not lead to an abatement of the wretched 'bit' nuisance.

At the Mint on Carson Street, a sufficient quantity of 1875-CC twenty-centers settled neatly on a small section of the cashier's vault-shelf in late winter 1876. At the current rate of distribution, those 1875 issues would last far beyond 1876, and probably never be totally exhausted by the time Congress repealed the twenty-cent law. Yet in March 1876, James Crawford, almost certainly on orders from Linderman, oversaw his coining crew turn a little less than 1,450 ounces of silver into 10,000 twenty-cent pieces.

There they sat, along with the remaining 2,500 to 3,500 1875 leftovers, all through 1876 and into early 1877. A handful of examples escaped. Some went to the Assay Commission back East, and some were distributed as favors, presumably to locals but possibly to supplicants out of the area.

Director Linderman's memo to Superintendent James Crawford, dated March 19, 1877, instructed Crawford to melt all remaining twenty-cent pieces at the Carson City Mint. It is believed that more than 99 percent of the ones dated 1876, and another 2,370 or so from 1875 were liquefied in a melting pot, lost forevermore.

1876-CC Twenty-Cent Piece Becomes a Regal Rarity

In 1893, Augustus G. Heaton introduced his treatise that launched a mintmark collecting movement. Heaton declared the 1876-CC twenty-cent piece to be 'very rare,' and worth at least 'two or three times' the price of the much lower mintage Philadelphia Proof issue from 1877. Following is a list of notable appearances and mentions of 1876-CC twenty-cent pieces in Heaton's era:

Like other great prizes in the U.S. coin series, the 1876-CC twenty-cent piece became a measure of the respectability and preeminence of a collection. In the March 1911 issue of The Numismatist, editor Edgar H. Adams reported that dealer, Elmer S. Sears, exhibited an Uncirculated 1876-CC twenty-cent piece. Adams said he knew of only four examples of this date and named the other three owners: John H. Clapp (whose father John M. Clapp had bought the S.L. Lee specimen in 1899), Virgil M. Brand, and H.O. Granberg -- all among the numismatic elite. In early 1914, at the American Numismatic Society's Exhibition of Coins in New York, distinguished Baltimore collector, Waldo C. Newcomer, displayed his 1876-CC twenty-cent piece. By then, a new price record had been established, when The United States Coin Company auctioned Malcolm N. Jackson's 1876-CC twenty-center for $250 in May 1913 (reportedly bought by Newcomer).

Twenty-two years later, in 1935, noted collector F.C.C. Boyd advertised in The Numismatist that he would sell his 1876-CC twenty-cent piece for $350. (Boyd hung onto the coin for 10 more years before it sold for $1,500 in 1945 in Numismatic Gallery's World's Greatest Collection sale.)

Three significant events in this date-denomination's history happened between 1950 and 1966:

Through the years, notable numismatists and some more obscure collectors have owned examples of the 1876-CC twenty-cent piece. Following is a partial list of past owners:

Q. David Bowers: "In the pantheon of American rarities the 1876-CC has been famous for a long time. The present writer recalls that in the 1950s the classic silver rarities were generally recognized as the 1894-S dime, 1876-CC twenty-cent piece (the 1873-CC dime without arrows was not widely known as only one exists), and the 1838-O half dollar. In later years, studies became more sophisticated; Walter Breen and others wrote much about rarity, with the result that, for example, the 1870-S silver dollar, with just nine or ten known, was recognized as being rarer than the 1876-CC twenty-cent piece. However, the twenty-cent piece still captured all the publicity. This situation has many equivalents elsewhere in coinage, such as the 1804 silver dollar with 15 specimens known, being called the King of American Coins, although in terms of rarity it is eclipsed by quite a few other silver and gold issues.

There was virtually no interest in collecting mintmarked coins in 1876, so not even the Mint Cabinet desired an example of the twenty-cent piece. The survival of pieces was strictly a matter of chance. It is thought that the 10,000 pieces made for circulation went to the melting pot, but that perhaps 20 or so were saved, possibly including pieces sent for the Assay Commission ceremony held early in 1877. It was not until later that any particular notice was given. In 1893 Augustus G. Heaton's A Treatise on Mint Marks recognized the variety and showcased it as 'excessively rare,' but there was no accompanying story. The issue remained a mystery and anyone looking at the Annual Report of the Director of the Mint could logically think that 10,000 had been distributed and that sooner or later an example would come to hand. However, by the time they were produced by the Carson City Mint, the denomination was rendered effectively obsolete, so apparently nearly all were melted. The destruction of these coins is probably the subject of the following request written by Mint Director Henry Richard Linderman on March 19, 1877, addressed to James Crawford, superintendent of the Carson City Mint: 'You are hereby authorized and directed to melt all twenty-cent pieces you have on hand, and you will debit Silver Profit Fund with any loss thereon.'

In 1876 at the Carson City Mint selected samples of all coins were set aside for examination by the annual Assay Commission, which met in Philadelphia on Wednesday, February 14, 1877. Presumably, only a few 1876-CC twenty-cent pieces were shipped east for the Commission. This group later probably constituted most of the supply available to numismatists. It seems likely that a few were paid out in Nevada in 1876-1877, accounting for a handful of worn and impaired pieces known today. The June 1894 issue of The Numismatist included this interesting filler: 'Three of the rare twenty-cent pieces of 1876 from the Carson City Mint have lately turned up in Uncirculated condition. It was not two days before they were incorporated into three of our leading collections where their presence is highly appreciated.'

In the early 20th century the collecting of mintmarks became more popular, and they were closely studied. Estimates of the rarity of the 1876-CC twenty-cent piece ranged from a half dozen to perhaps ten. As is so often true in numismatics, facts were scarce and guesses were aplenty. Often a guess or estimate was converted by later writers into fact.

The situation remained thus until about 1956 or 1957 when Tom Warfield, a well-known Maryland dealer, found a group of Mint State coins in Baltimore, suggesting that these may have been Assay Commission coins. Seeking not to disturb the market he sold them privately, with four of them going to John J. Ford, Jr., a partner with Charles Wormser in the New Netherlands Coin Company; two of them going to Stack's in New York City; and four going to me. Each of us contacted various clients, and soon they were all gone. Each piece was a beautiful Gem with rich luster on both sides.

Today the 1876-CC twenty-cent piece remains a very famous rarity, its attraction undiminished despite some other silver issues from various mints being harder to find. Nearly all are Mint State."

The 1876-CC is ranked No. 16 in the popular reference 100 Greatest U.S. Coins by Jeff Garrett and Ron Guth (second edition published 2005).

The example to the left was sold by Stack's Bowers Galleries in the E. Horatio Morgan Collection, where it realized $456,000.