I continue my “tour” through the 68th (2015) edition of A Guide Book of United States Coins. In this series I have been going page by page through this familiar red-covered reference, giving comments that you can tie in with pictures and other information in the book itself. The Guide Book first saw the light of day in 1946 (cover date 1947), edited by Richard S. Yeoman. At the upcoming Whitman Coin & Collectibles Expo in Baltimore later this month, the 2016 edition will be launched. I probably will continue in the 2015 edition, however, at least for a time, as it takes a while for the new edition to be distributed.

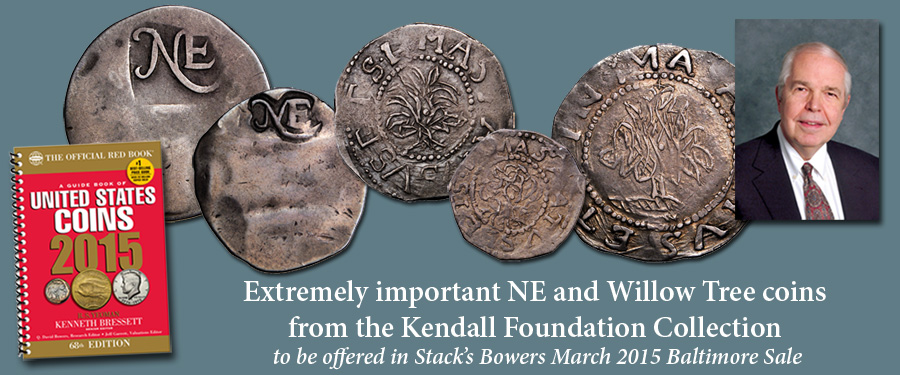

This week I am on page 37, the Coinage of Massachusetts. Authorized in 1652 by the General Court of Massachusetts, a colony of Great Britain, coinage was created in four separate types. The earliest or NE pieces had NE on one side, stamped with a punch, and on the other side the denomination expressed as III (threepence), VI (sixpence), or XII (shilling). These were made by taking a blank silver planchet, applying a punch on one side and then turning the planchet over and at the other end (not directly opposite the first punch) impressing the second punch. Such pieces were effective in circulation and thousands were made of the shilling. Today the threepence, unique, is a classic rarity and only eight are known of the sixpence.

Prior to this coinage, and continuing for a while afterward, coins were scarce in circulation. When found, they were silver (mainly) and gold issues of Spanish-American countries and similar issues from Great Britain, France, Italy and other European nations. While coins changed hands, most transactions were done on the barter system. On May 27, 1652, the aforementioned coinage act was passed, providing that a mint be established. John Hull was appointed mintmaster. In his diary he noted:

“Also upon occasion of much counterfeit coin brought into the country, and much loss accruing in that aspect (and that did occasion a stoppage of trade), the General Court ordered ‘a mint to be set up and to coin it, bringing it to the sterling standard for fineness, and for weight every shilling to be three pennyweight, that is, 9 pence at 5 shillings per ounce.’ And they made choice of me for that employment, and I chose my friend, Robert Sanderson, to be my partner, to which the court consented.”

On June 22, 1652, the committee met and determined that a mint house would be built upon land owned by John Hull. It was to be 16 feet square, 10 feet high, and “substantially wrought.”

The simple nature of the first NE coins caused problems and on October 19, 1652, an act was passed that provided:

“For the prevention of washing [dissolving the silver metal by nitric acid] or clipping [trimming slivers of silver from the edge] of all such pieces of money, as such shall be coined within this jurisdiction:

“It is ordered by the Court and the authorities thereof that henceforth all pieces of money coined as aforesaid shall have a double ring on either side, with the inscription MASSACHUSETTS and a tree at the center on one side and, NEW ENGLAND and the year of our Lord on the other side…”

While clipping and washing of the NE coins seems to have been a problem at the time, today the examination of surviving pieces shows little evidence of such damage. Indeed, later issues are more usually seen clipped.

On the numismatic scene the NE coins were widely sought when the hobby of coin collecting became popular in the late 1850s. By this time the coinage was well known to historians, through the 1839 book by Joseph Felt, a study that, remarkably, is still usable as a standard reference today, although copies are not easily obtained. There are many sources for information on Massachusetts coinage, an easy entrée to such being the website of Notre Dame University in Indiana, devoted to colonial coins and paper money and maintained by Louis E. Jordan. This lists many other references. Jordan’s book, John Hull, The Mint and the Economics of Massachusetts Coinage, is recommended for any numismatic library. See page 439 of the Guide Book for additional titles. Another book that is absolutely essential is The Early Coins of America by Sylvester S. Crosby, originally published in 1875 and reprinted several times since. This is another volume that is still useful today.

Following the call for a new design this took place and involved preparing designs as well as setting up a coining press (instead of using hand punches). Louis E. Jordan suggests that this took time and that it was not until 1654 that the new coinage commenced. Thus was introduced the Willow Tree series, known as such numismatically and issued in denominations of III, VI, and XII. The tree as specified by regulation has no particular shape and consists of curls and squiggles, not identifiable as any botanical species, certainly not as a willow. Joseph Felt in his 1839 book gave it no particular designation, nor did Montroville W. Dickeson in his 1859 American Numismatical Manual. W. Elliot Woodward in his sixth sale, 1865, suggested a “palmetto” tree. The earliest “Willow Tree” use found by Sydney P. Noe, whose works on Massachusetts silver were published by the American Numismatic Society, was in Woodward’s 1867 sale of the Joseph Mickley Collection. Today in 2015 the Willow Tree name is firmly established and little is said about it.

It seems that the blank silver disks were placed into a rocker press, which forced a curved top die against a curved or flat bottom die. The pressure point moved as the roller moved, and greater force could be exerted than could be done with one flat die striking another flat die. Certain Willow Tree and later coins are gently elongated and slightly “wavy” giving credence to this possibility. Today all Willow Tree coins are rarities, and the appearance of a single example at auction typically attracts a lot of attention. Of the threepence just three are known, one of which we sold in October 2005, VF grade, for $632,000. The Willow Tree sixpence is a rarity as well, with about 14 known. The shilling is the only readily collectible denomination. An example in Fine or better condition typically crosses the $100,000 mark.

I will see you next week and will describe the Oak Tree coinage.