One of the many questions I am asked is: "Why is having the pedigree of rare coins and currency you sell important?" The pedigrees of numismatic items, works of art, jewelry, or other collectibles are valuable assets. They can record ownership from the day an item was issued or first sold and contain a history of subsequent owners. Most old-time collectors retained pedigrees, as they have been important to buyers through the decades. They are still important, right up to the present day, and the retention of pedigrees into the future will continue to add value to a numismatic item.

I will discuss numismatic items as they are what I am most familiar with. Collections in America, as well as the rest of the world, were mostly assembled by those who could afford to put items away and save them for the future. When we examine the early days of America and into the Industrial Revolution, collectors had many handicaps that do not exist today. First, a collector had to have some wealth to put away items. Communication was more difficult; it was mostly face-to-face, or by correspondence that took a long time to go from one person to another. In the very early days, those who dealt in coins were usually jewelers or buyers of precious metal, or in the currency exchange business. Others were book dealers or art dealers. Some were collectors as well. There was little if anything published that collectors could refer to, and they were lucky to have access to any information on coinage and coinage history.

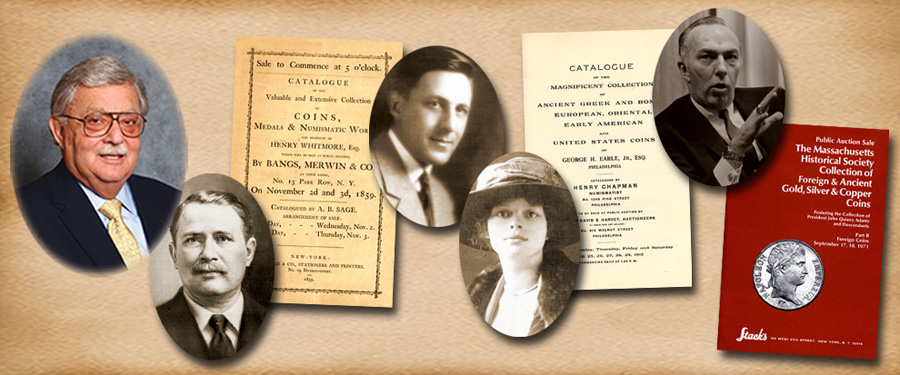

Dealers of course experienced the same restrictions. Dealerships were located only in a few major cities or near them, auctions were few, and price lists were originally handwritten to the client, or in rare cases distributed to only a few. After the Civil War, some things changed. People earned a bit more, more wealth was accumulated, and important dealers in numismatics opened shops in Philadelphia, New York and Boston. These shops attracted mostly local collectors. Auction sales became more prevalent and a few lists of coins were distributed. Many of these publications listed the famous collectors who had these coins for sale, and often previous owners were listed in the catalogs. The dealers felt that showing a pedigree established the worthiness of the coin, especially if the previous collector was known to be well educated in the fields he collected. A pedigree to an astute collector could show how a coin rated.

Nineteenth and early twentieth century collectors learned more about rarity, value and grade as the hobby grew. Things were changing. The advent of electricity offered better lighting for collectors to examine and learn from their coins. More companies began holding auctions and auction catalogs became sources of information that wasn’t in any books. There were collectors who were so dedicated to collecting certain series, that they compiled reference texts. This occurred in the beginning with colonial coins, half cents and large cents, and then with other series. Famous names as Beistle, Ryder, Crosby, and others all published books on their collections. Beginning in the late nineteenth century the American Numismatic Association held annual meetings in different cities around the country. The American Numismatic Society established a museum and home in New York, and welcomed collectors to see their exhibits (often donated by their elite membership) and published a monthly journal expanding the printed references of different series. The Society’s publications covered not only coins of America, but provided education for those who collected coins of the ancient and foreign series — the availability of knowledge in English expanded collecting in more series. Often these publications referred to previous owners thereby establishing pedigree lineage.

The growth of the hobby led people to search their change, the drawers in their homes where a coin or a bag of coins might have been set aside because they were different general change. Or items might be found at a bank or jeweler while shopping, doing daily chores or traveling. While these coins from outside numismatic circles did not have pedigrees, as they made their way into collections their history could begin to be recorded. And once placed in a collection and then sold, usually by auction, a coin’s lineage could then be traced as it moved from one collection to another. I will continue my discussion of pedigrees next week.